Pikeville, Tennessee

AARP Livable Communities Grant Award

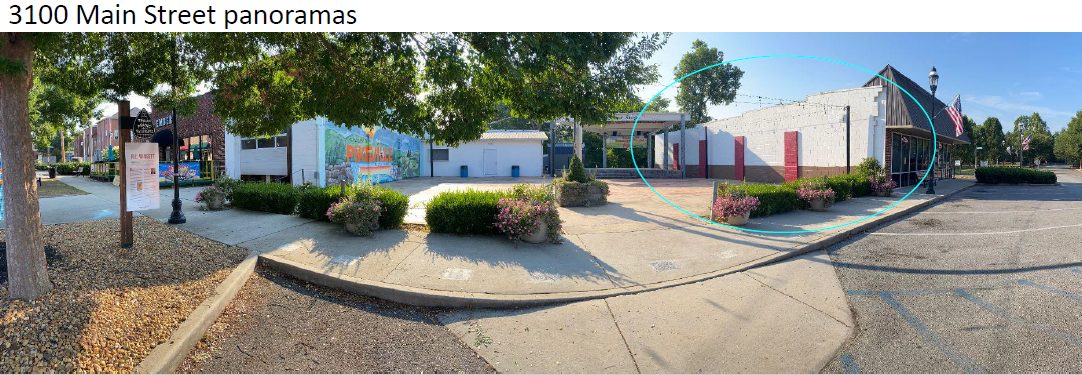

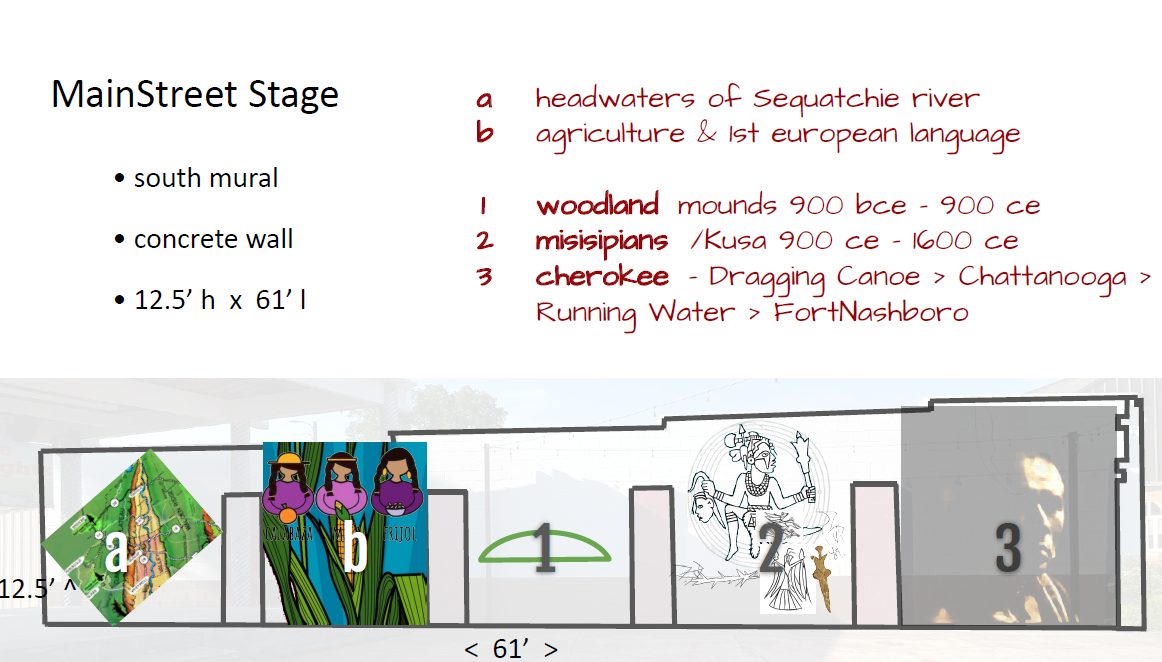

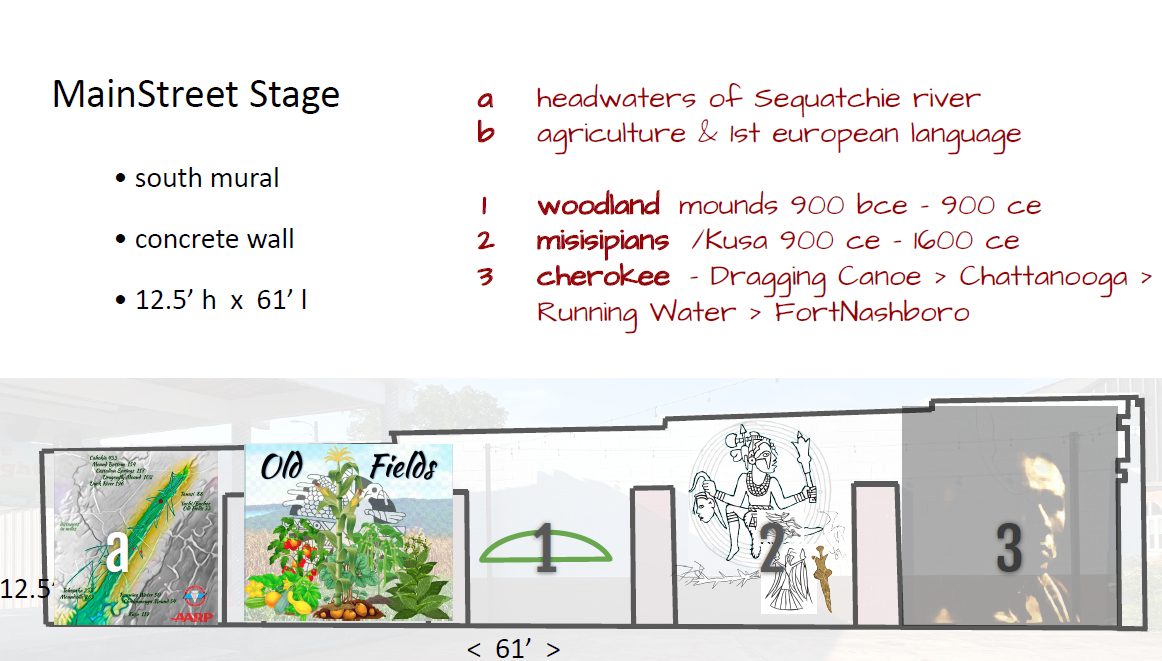

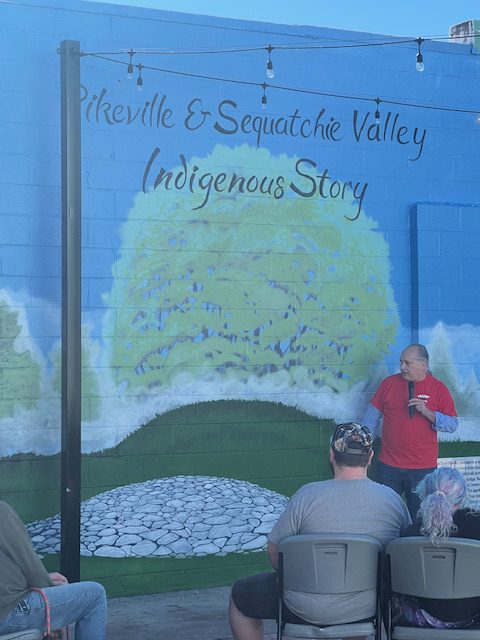

The City of Pikeville was proud to announce that on May 9, 2024, it was selected as a recipient of the AARP Livable Communities Grant in the amount of $12,000. These funds were designated to support the creation of a mural honoring local Indigenous history, painted on the southern wall beside the Main Street Stage, facing the iconic Welcome to Pikeville mural.

This initiative reflected Pikeville’s ongoing commitment to building a more livable and inclusive community for all residents. The mural became one of several projects aimed at enhancing quality of life and celebrating the town’s cultural heritage. The City collaborated with a selected artist skilled in Native American art, along with community members, to bring the vision to life.

The completed mural showcases the ancient history of Pikeville, celebrating the community’s past, present, and future — a vibrant reflection of the heart and soul of our city.

Honoring Indigenous History Through Art

A Mural of Memory, Resistance, and Resilience

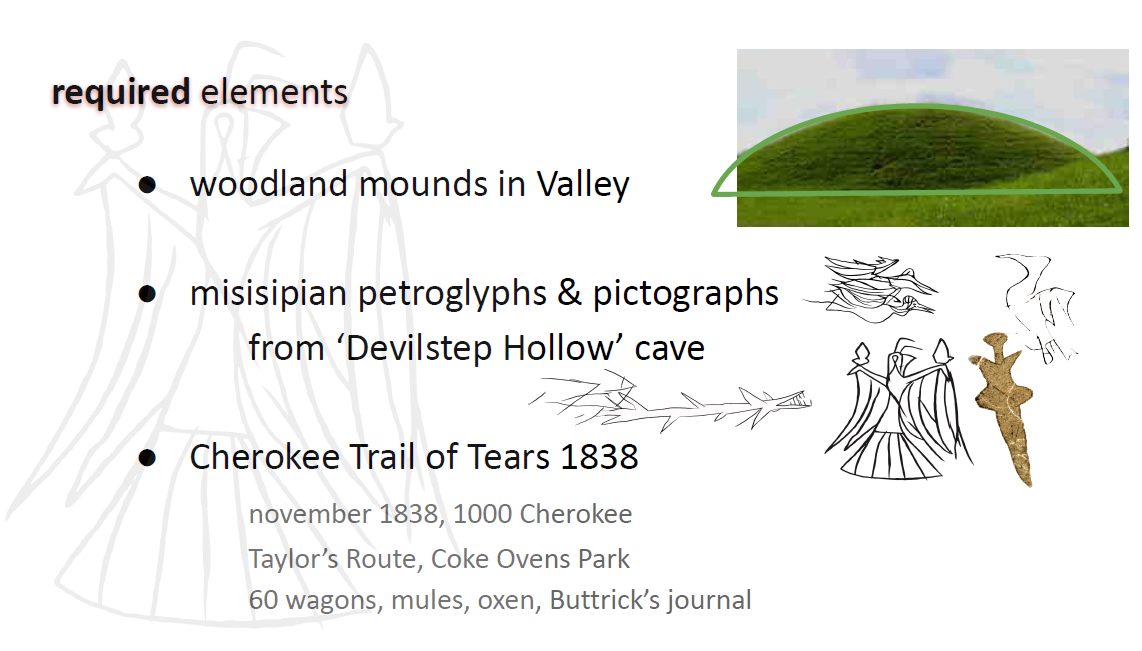

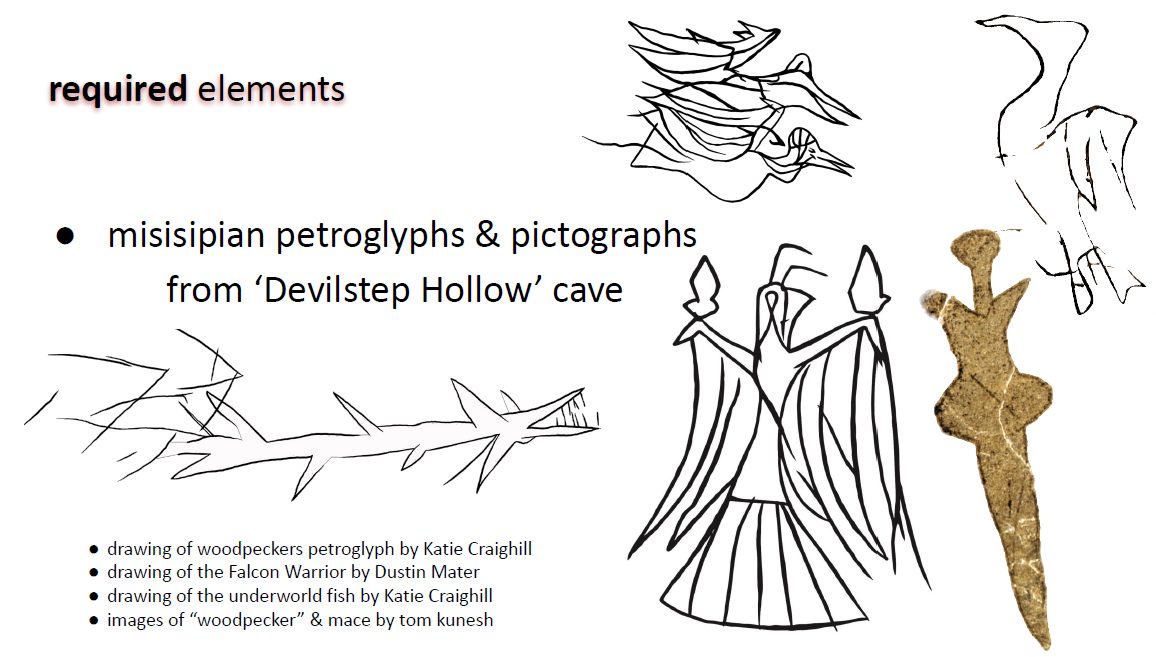

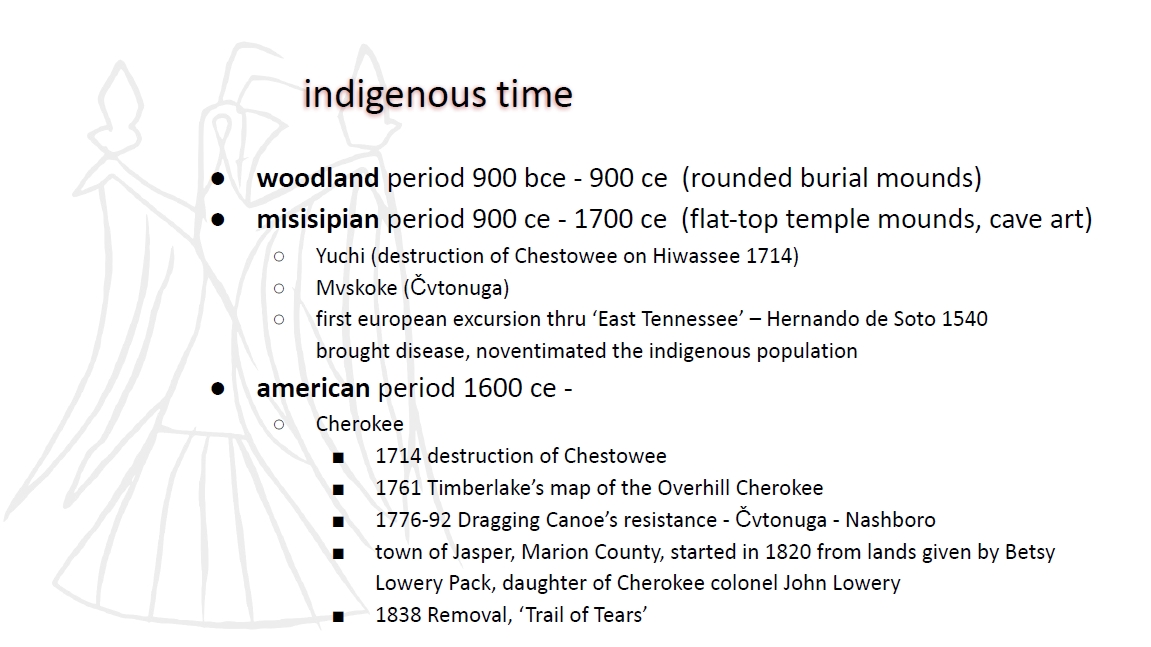

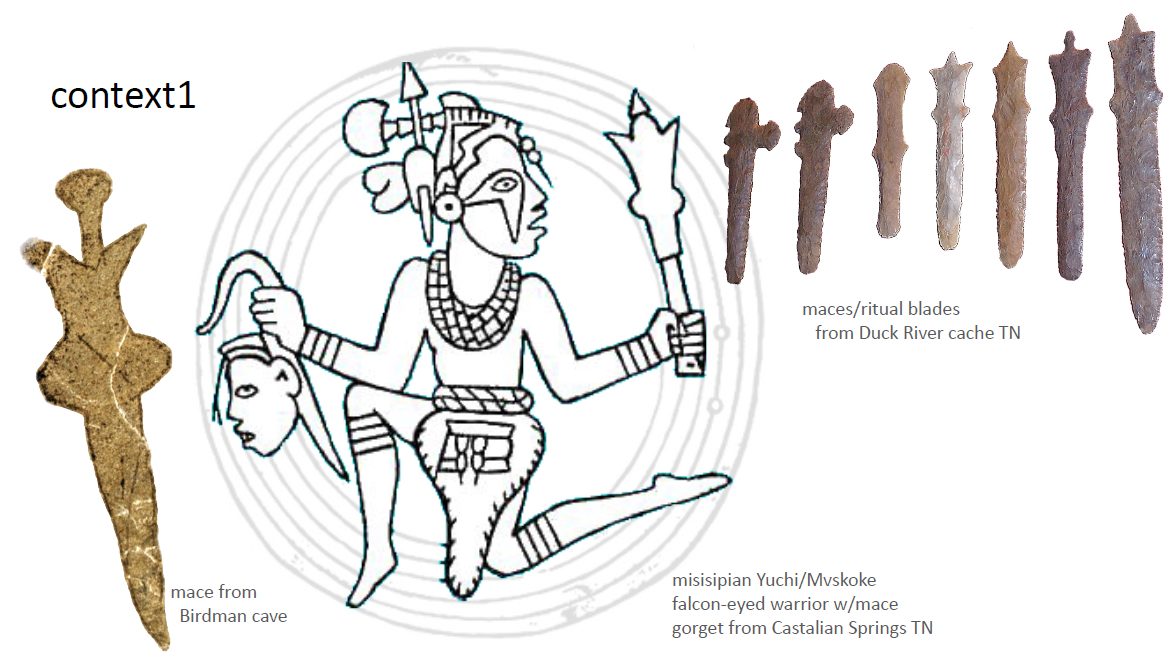

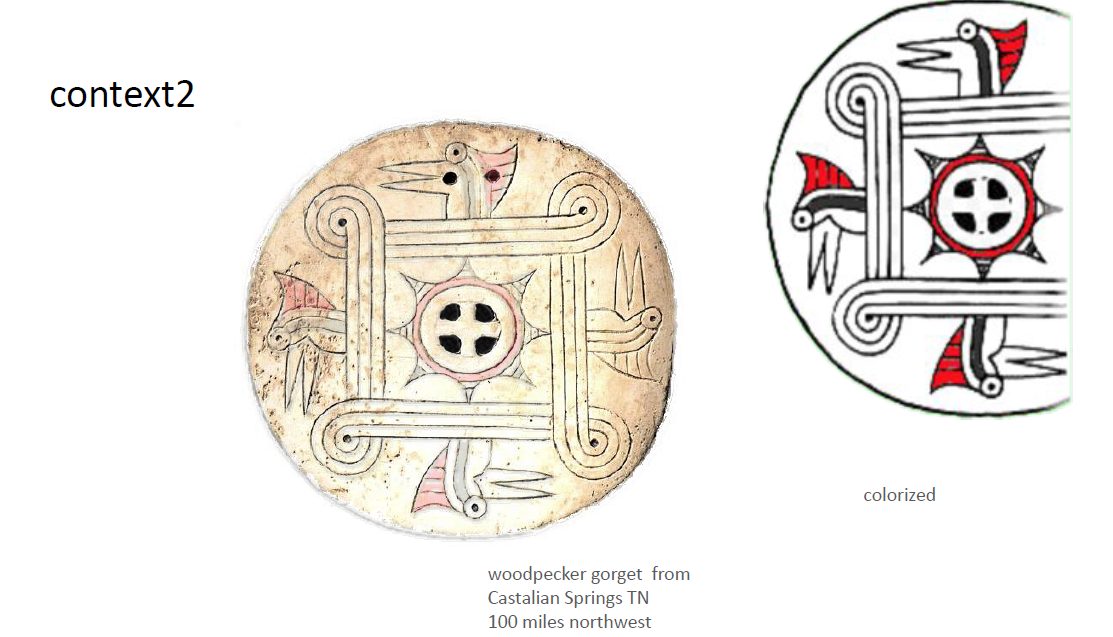

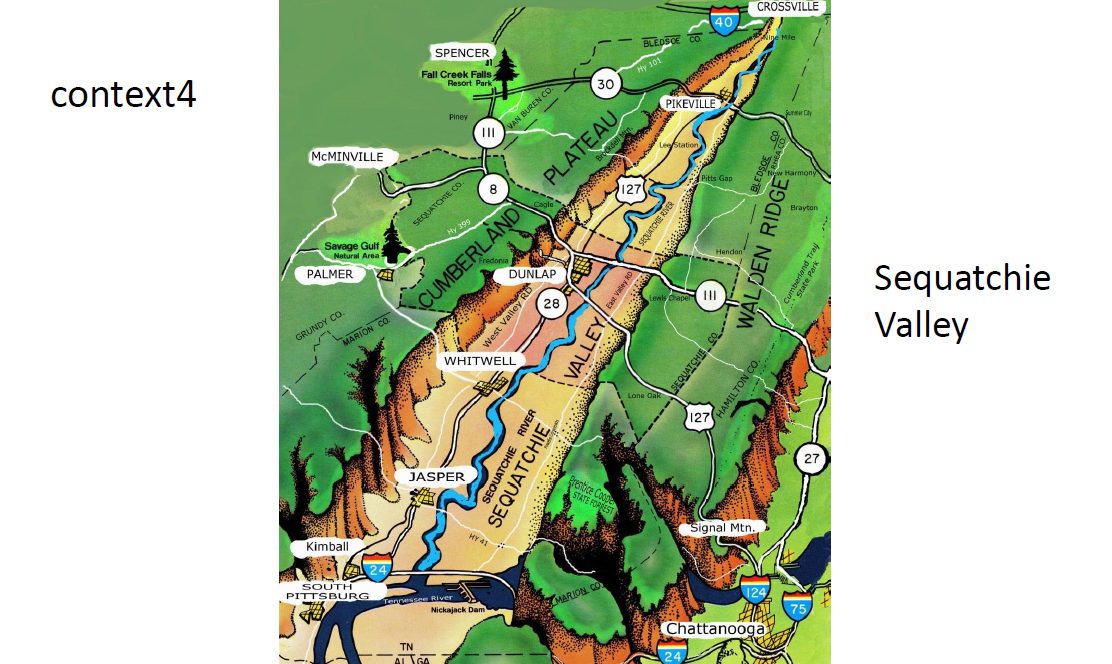

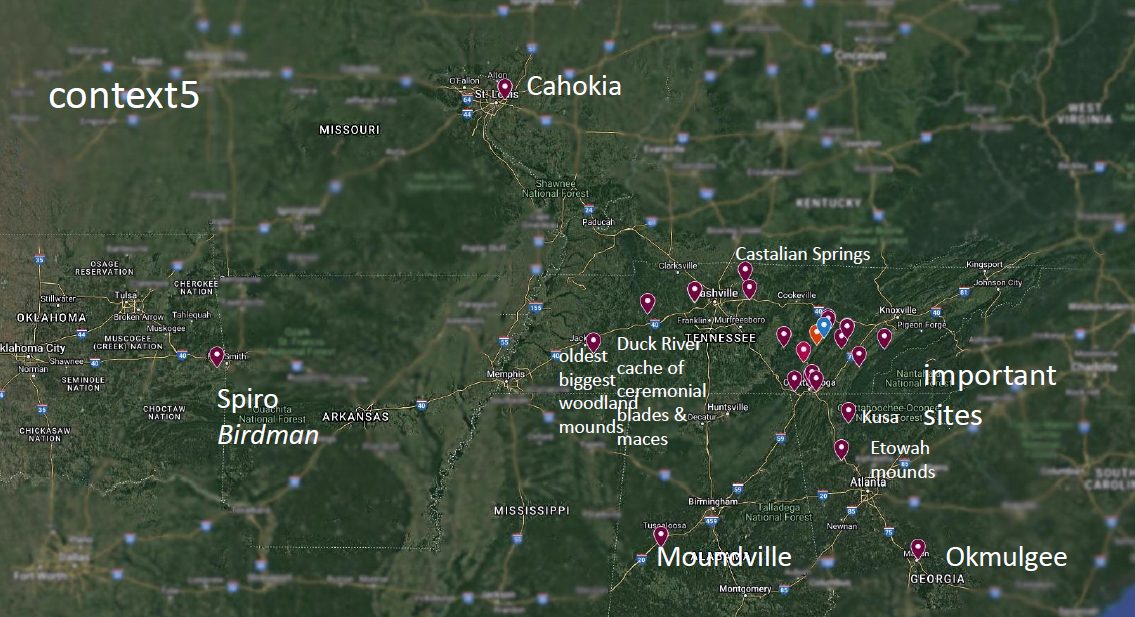

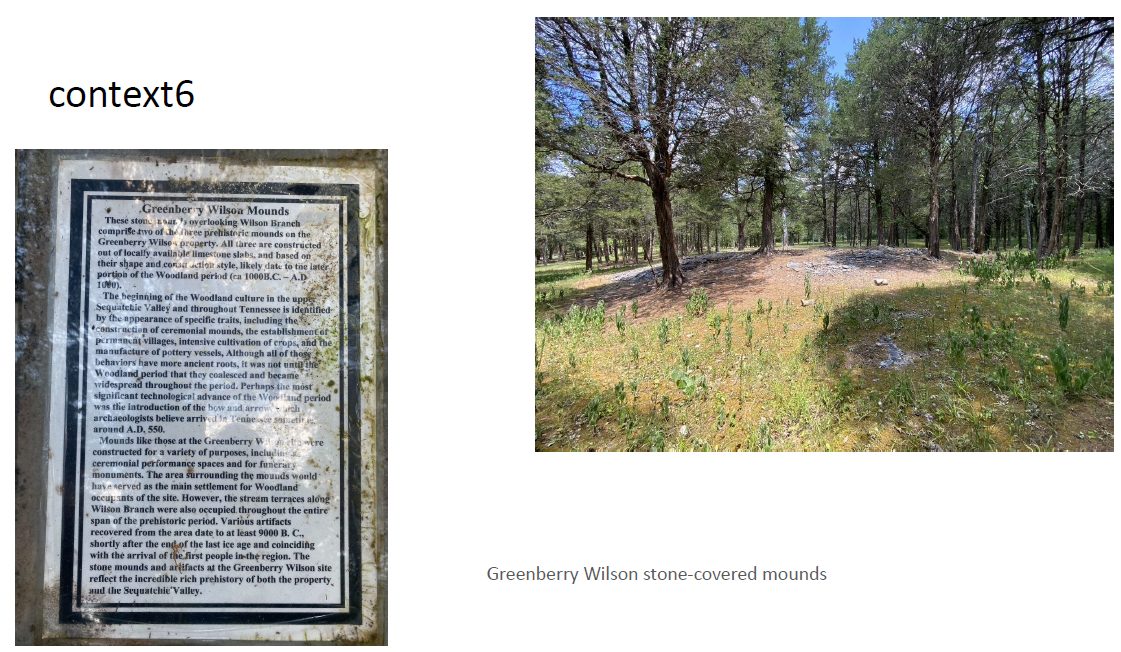

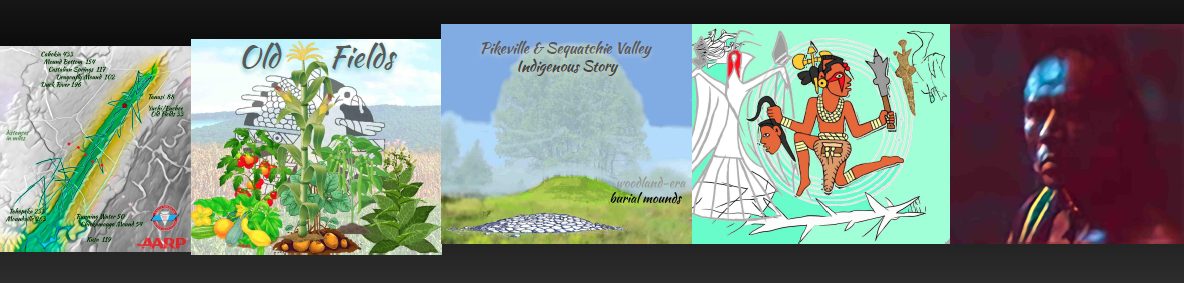

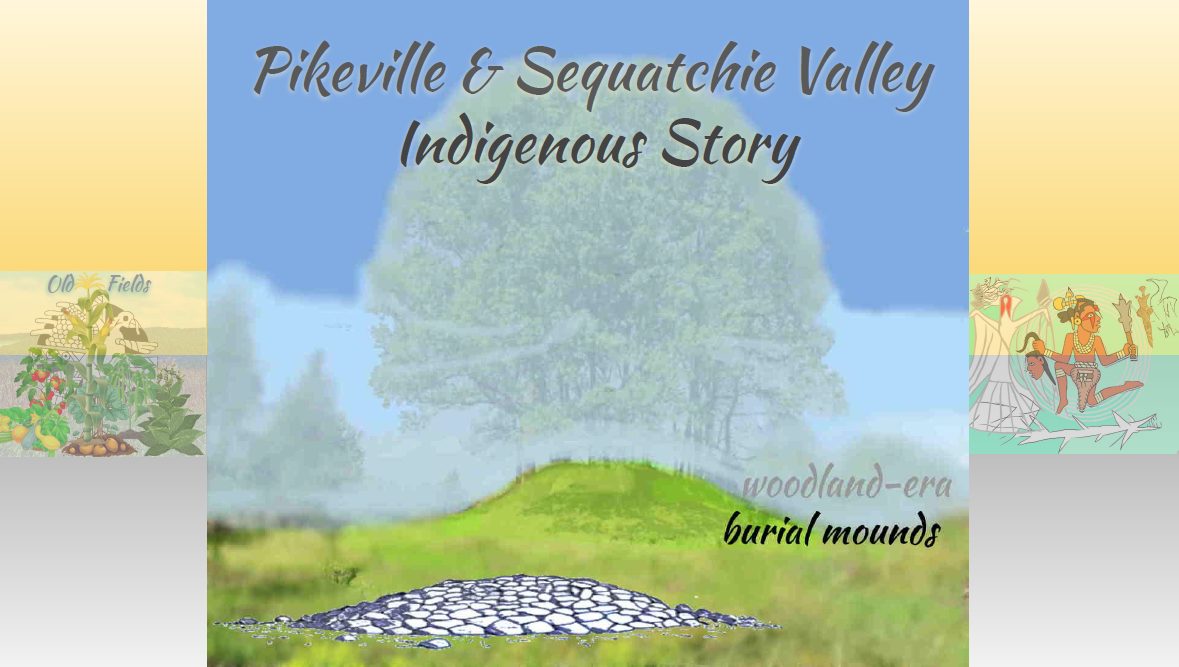

This mural was designed to honor the deep and complex history of the Sequatchie Valley, introducing visitors to the extraordinary — and often overlooked — Indigenous art and heritage of the region. At its heart are the ancient drawings from Devilstep Hollow Cave, located just 20 miles north of Pikeville. These cave images, including the Birdman, Fishmonster, and ceremonial mace carvings, represent some of the most striking examples of prehistoric art in North America.

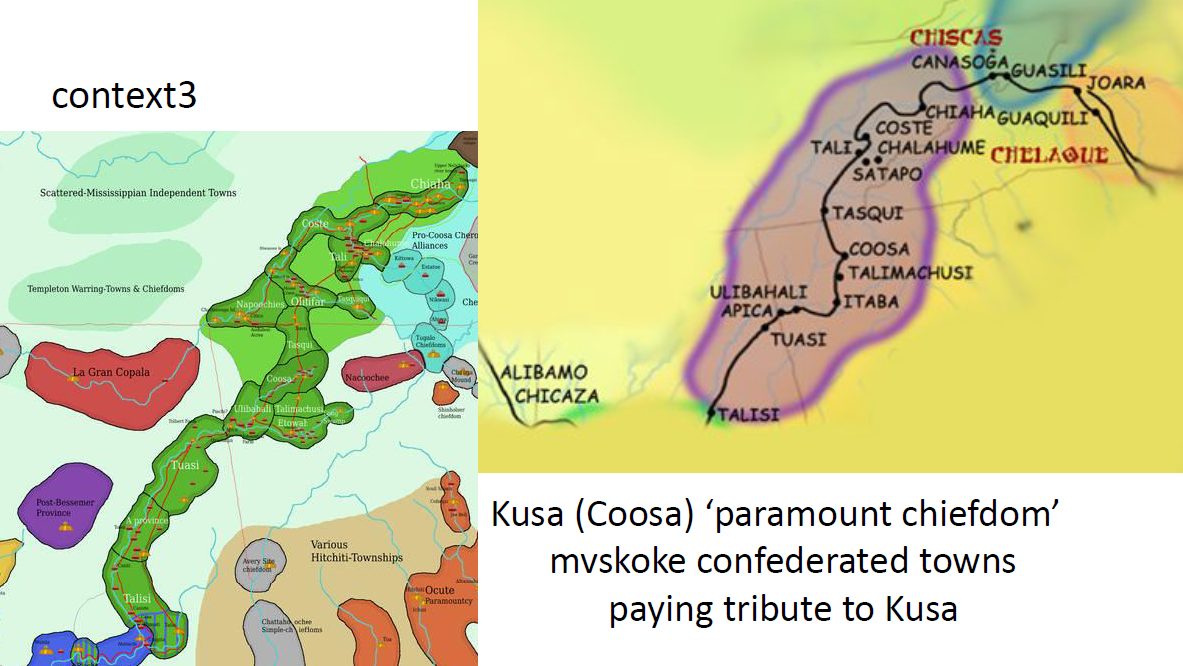

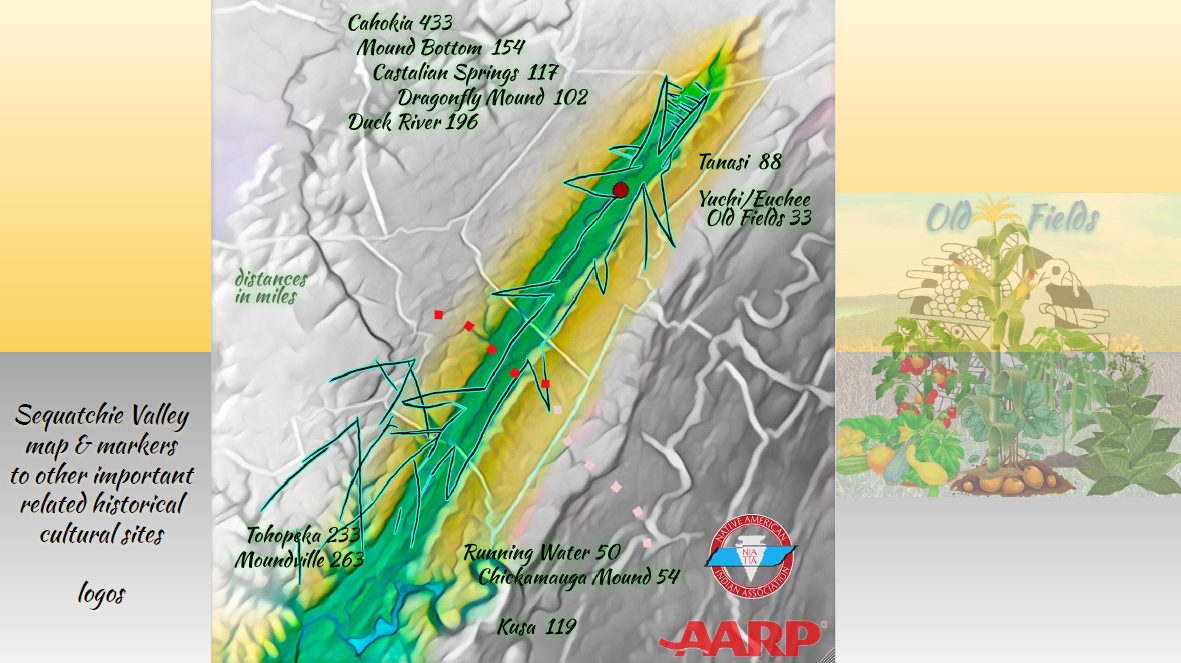

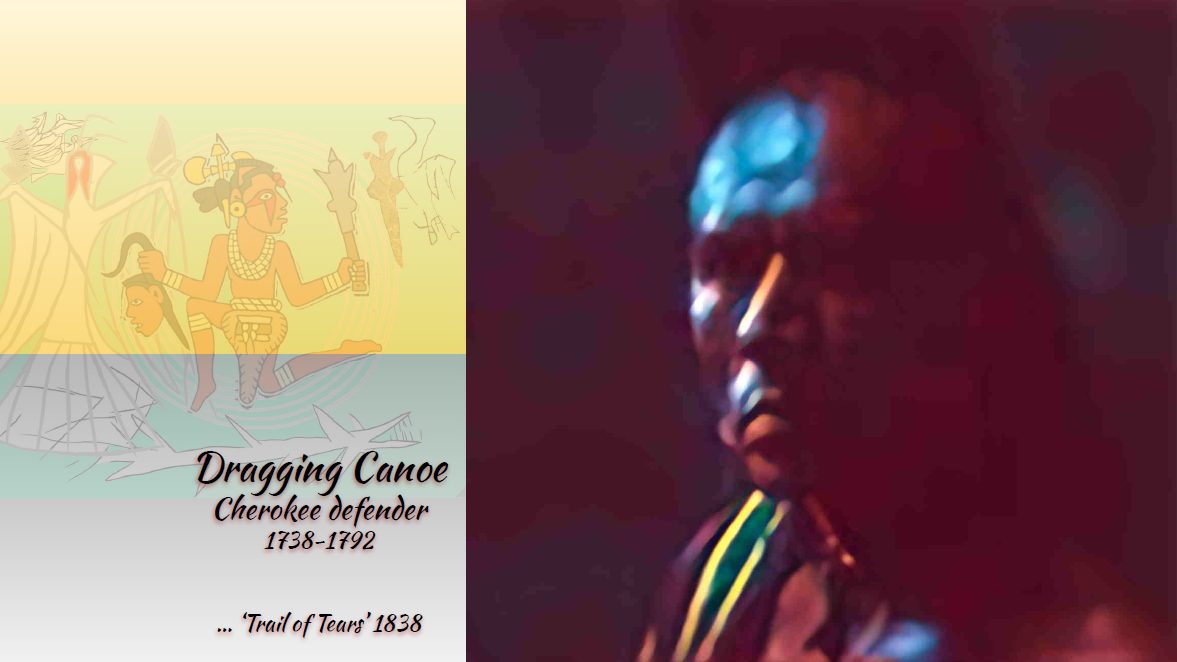

Surrounding panels depict the Old Fields — the original agricultural crops cultivated by the Mississippian peoples between 900 and 1500 CE — alongside burial mounds, ceremonial gorgets from Castalian Springs, and an imagined portrait of Dragging Canoe, the famed resistance leader of the Chickamauga Cherokee. These elements reflect the strength, artistry, and struggle of the Yuchi and Muscogee peoples who lived in this valley long before their forced relocation during the Cherokee Removal.

One of the mural’s most dramatic scenes features a Mississippian/Muscogee warrior, inspired by a nearby gorget, standing with a battle mace raised in one hand and the head of a vanquished foe in the other. The mace mirrors those found in Devilstep Hollow Cave and the Duck River cache, linking Pikeville’s landscape to a broader ceremonial and cultural tradition.

Another powerful element is the abstract silhouette of Dragging Canoe, a visual tribute to Indigenous resistance and a reminder of the racial cleansing that displaced entire nations. This mural invites reflection and dialogue across generations — encouraging empathy, understanding, and a deeper appreciation of the histories that shaped our region.

A portion of the mural also serves as a map of the Sequatchie Valley, marking two key crossing points from the 1838 Trail of Tears. It offers a guide for future educational pilgrimages to nearby Indigenous sites, helping place Pikeville’s story within a larger cultural context that honors diversity, memory, and belonging.

Mural Unveiling: A Moment of Reflection and Pride

On Saturday, November 16th, the community of Pikeville gathered to unveil the Indigenous History Mural — a powerful tribute to the original stewards of this land. Designed and researched by Tom Kunesh, the mural brings to life the stories, symbols, and traditions of Indigenous peoples whose histories have long been overlooked. Each panel offers a vivid glimpse into the daily lives, struggles, and cultural richness of the Yuchi, Muscogee, and Chickamauga Cherokee, honoring their resilience and legacy.

The unveiling was marked by a deep sense of pride and unity. Residents stood together in recognition of a shared responsibility: to preserve and uplift the histories that shaped Pikeville’s identity. The mural now stands as a visual testament — not only to the past, but to the enduring diversity and strength that continue to define the community.

Another powerful element is the abstract silhouette of Dragging Canoe, a visual tribute to Indigenous resistance and a reminder of the racial cleansing that displaced entire nations. This mural invites reflection and dialogue across generations — encouraging empathy, understanding, and a deeper appreciation of the histories that shaped our region.

More than art, this mural is a legacy. It invites reflection, sparks dialogue, and inspires future generations to learn, honor, and carry forward the stories of the Indigenous peoples who helped shape the soul of Pikeville.

Interactive Mural Experience

Indigenous History Comes to Life Through QR Code Videos

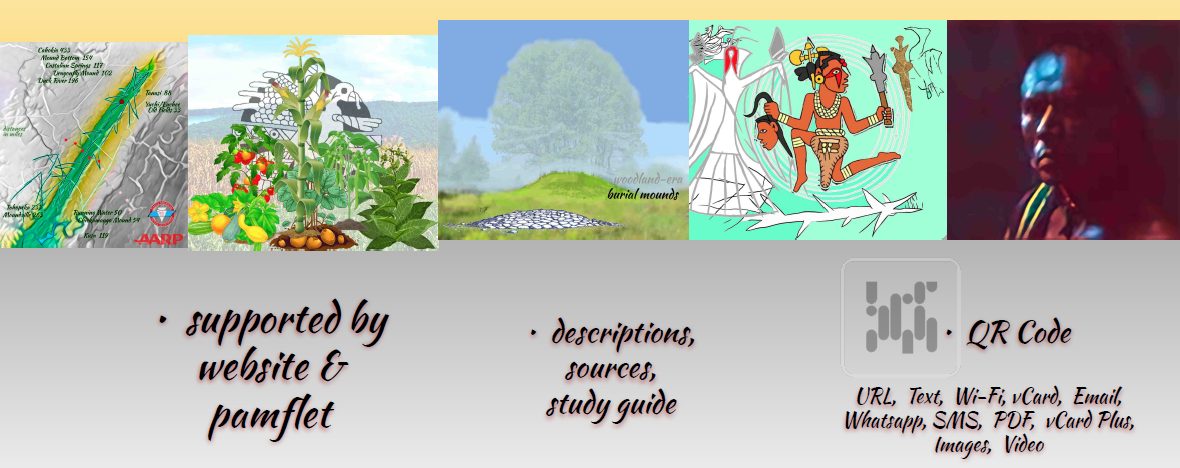

The Indigenous History Mural offers more than visual storytelling — it’s an interactive journey through the rich and complex heritage of the Sequatchie Valley. At the base of each panel, visitors can scan six QR codes, unlocking short videos that deepen the experience.

The series begins with an introduction to Pikeville’s Indigenous story, setting the stage for a powerful exploration. From there, viewers can follow the Trail of Tears Path, uncover the agricultural legacy of the Old Fields, learn about the Yuchi and Muscogee peoples, venture into the sacred imagery of Devilstep Hollow Cave, and conclude with the story of Dragging Canoe, a legendary resistance leader.

Each video offers a deeper lens into the art, resilience, and history of the region’s original inhabitants — creating a meaningful, educational experience for all who visit.

Mural Journey: From Vision to Completion

We’re proud to share the creative journey behind Pikeville’s Trail of Tears mural, now completed and standing as a powerful tribute to the Cherokee people and their historic journey through the Sequatchie Valley.

Below, you’ll find a series of slides documenting the early design and preparation work — from initial sketches and research to the hands-on artistry that brought this vision to life. These behind-the-scenes moments offer a deeper appreciation for the care, collaboration, and cultural respect that shaped every brushstroke.

This mural now serves as a lasting landmark — a visual reminder of resilience, remembrance, and the importance of honoring Indigenous history in our community.